Image ©2020 by B H Triber |

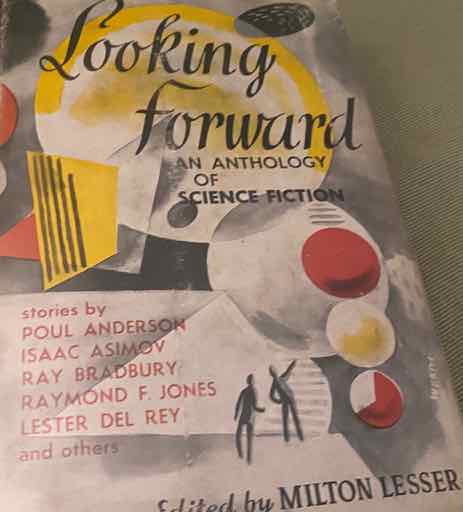

Review of editor Milton Lesser’s Atomic Age Anthology, Looking Forward |

I found an old collection of early 1950s SF short stories at a hole in the wall shop in Salem, Massachusetts a month back. The title of the collection is “Looking Forward; an Anthology of Science Fiction” edited by Milton Lesser. (Known best for his Chester Drum mysteries under the pen name of Stephen Marlowe, Lesser also worked under a number of other pen names.) Now, the names on the cover certainly promise a good read: Anderson, Asimov, Bradbury, Lester Del Rey… And the table of contents reads like a Who’s Who of golden age sci-fi writers. Twenty shorts by greats like Jack Williamson (Grandmaster of SF), Lewis Padgett (also known as the writing duo of Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore), Walter M. Miller Jr. (“A Canticle for Leibowitz”, 1959), Robert Lowndes (editor of golden age SF magazines Science Fiction, and Future Science Fiction), Murray Leinster (who had just introduced science fiction to the universal translator in his 1945 novella “First Contact”), Jack Vance (multiple Hugo- and Nebula-award winner), and Gordon R. Dickson (who would later win Hugo and Nebula awards as well). Stranger still, this copy had once belonged to the MIT Science Fiction Library. Somehow, this book and I have crossed paths throughout eastern Massachusetts for the last 50 years without connecting until now, despite my having worked in the MIT community for 20 years. It will join a couple other volumes from the same collection I’ve obtained since they were liquidated from MIT.

Looking Forward, with its deceptively bland title, contains a variety of creative fiction that would never be found together today in a single anthology. Mostly written between 1949 and 1952, they all have a very unique generational lens: World War II was fresh on everyone’s minds, they were stuck in the adolescence of the Cold War, with Korea actively claiming American lives. Atom bomb drills were routine, and mandatory blackouts with wailing air raid sirens were still common practice when staring at the looming threat of a Soviet Union that could drop the H-Bomb undetected by high-altitude aircraft, long before a counter-strike deterrent had been deployed. It was the Wild West of atomic diplomacy, and these stories are filled with that existential angst, newly discovered by the inheritors of Oppenheimer’s legacy. (By the time I was born, we were entwined in an unflinching web of foreign policy that ensured the world would be destroyed should anyone blink.)

Being a product of its unique moment in time, the stories are varied in ways that today’s sci fi anthologies are not. Of course there are aliens and time travelers, game shows and highways to nowhere, and a fourth-wall breaking writers’ group. And, in the middle of it all, an argument for sending humans to the moon, and an argument for not sending humans to the moon. But there is also a breathable atmosphere on Mars (an idea that held for anther decade), and a dystopic alien-ruled 1950’s Earth that’s a cross between 1984 and Children of the Corn.

It’s a good read, if somewhat dated by callbacks to long-retired technologies — rotary phones and crystal sets come to mind. Perhaps in today’s age, these shorts can be looked at as period pieces, or perhaps the quaint seed of a future tube-punk movement. The style of the stories are dated, some almost sterile of emotion. Sometimes the story is so birthed of its time, it loses significance, like Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s “The Little Creeps”, set in post-WW II Japan with a booby-trapped Russian-Chinese river valley as its fulcrum. Sometimes the story transcends time, like Lewis Padgett’s “We Kill People”, which could be adapted as a modern cyberpunk with few changes.

Even if you can’t find a copy of “Looking Forward”, I strongly encourage you to look up the authors mentioned here. The science fiction of their era influences what follows in the 1960’s and 1970’s, which is ultimately the seed of today’s sci-fi.

Happy reading!