|

|

Editor’s Note: The following work is in the public domain. I have painstakingly duplicated and edited this piece because, although it is freely available from other sources, they are rife with typographical errors. Please contact me if you discover any errors you would like to report.

|

|

|

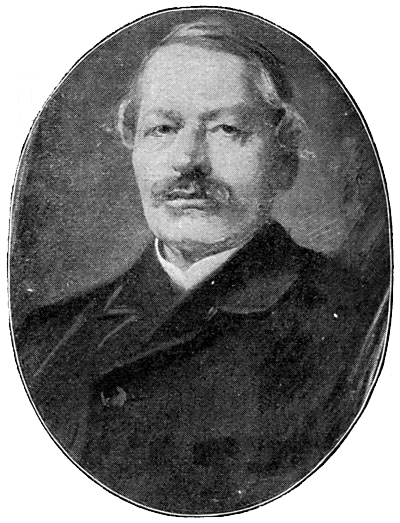

Image by Gabor [Public domain],

via Wikimedia Commons

|

Notes on this edition: Gustav Freytag, in this edition of his Technique of the Drama, exhibits strong German nationalism, borderline racism, classism, and blatant sexism, that, as an editor, I sometimes found challenging and insulting. However, it should be noted that, despite these shortcomings, the remainder of the work may still be considered valuable for the modern manner in which it approaches drama as a science and artform. Freytag was a man of the Nineteenth Century, and his biases should be considered within that frame of reference. They should in no way devalue this treatise on the theatre. It should remain needless to point out, but necessary for legal and other reasons, that the Editor in no way agrees with, promotes, or otherwise encourages Freytag's racial and political points of view.

Wherever possible, incorrect and archaic spellings, and capitalizations (or lack thereof) in the original manuscript have been preserved and so noted. Terms, titles, and quotations in other languages have been italicized for improved readability. Endnotes, which in the original edition were in a Notes section at the end of the manuscript have been preserved on a separate Notes page and linked appropriately for readability.

|

|

|

|

FREYTAG’S

TECHNIQUE OF THE DRAMA

AN EXPOSITION OF DRAMATIC

COMPOSITION AND ART

BY

DR. GUSTAV FREYTAG

AN AUTHORIZED TRANSLATION FROM THE SIXTH GERMAN EDITION

BY

ELIAS J. MACEWAN, M.A.

THIRD EDITION.

CHICAGO

SCOTT, FORESMAN AND COMPANY

1900

|

|

COPYRIGHT, 1894

BY S. C. GRIGGS & COMPANY

PRESS OF

THE HENRY O. SHEPARD CO.

CHICAGO

|

|

CONTENTS.

| |

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE.

|

| |

INTRODUCTION. — Technique of the drama not absolute. Certain craftsman’s skill of earlier times. Condition of present time. Aristotle’s Poetics. Lessing. The great dramatic works as models.

|

CHAPTER I. — DRAMATIC ACTION.

|

|

Part 1.

|

The Idea. — How the drama originates in the mind of the poet. Development of the idea. Material and its transformation. The historian and the poet. The range of material. Transformation of the real, according to Aristotle.

|

|

Part 2.

|

What is Dramatic? — Explanation. Effects. Characters. The action. The dramatic life of the characters. Entrance of the dramatic into the life of men. Rareness of dramatic power.

|

|

Part 3.

|

Unity. — The Law. Among the Greeks. How it is produced. How the unity of historical material is not secured. False unity. Where dramatic material is to be found. The character in the modern drama. Counter-play and its danger. Episodes.

|

|

Part 4.

|

Probability. — What is probable. Social effects of the drama. The strange. The marvellous. Mephistopheles. The irrational. Shakespeare and Schiller.

|

|

Part 5.

|

Importance and Magnitude. — Weakness of characters. Distinguished heroes. Private persons. Degrading the art.

|

|

Part 6.

|

Movement and Ascent. — Public actions. Inward struggles. Poet dramas. Nothing important to be omitted. Prince of Homburg. Antony and Cleopatra. Messenger scenes. Concealment and effect through reflex action. Effects by means of the action itself. Necessity of ascent. Contrasts. Parallel scenes.

|

|

Part 7.

|

What is Tragic? — How far the poet may not concern himself about it. The purging. Effects of ancient tragedy. Contrast with German tragedy. The tragic force (moment). The revolution and recognition.

|

CHAPTER II. — THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE DRAMA.

|

|

Part 1.

|

Play and Counter-Play. — Two halves. Rise and fall. Two kinds of structure. Drama in which the chief hero leads. Drama of counter-play. Examples. Spectacleplay and tragedy.

|

|

Part 2.

|

Five Parts and Three Crises. — The introduction. The exciting force (moment). The ascent. The tragic force or incident. Falling action. The force or motive of last suspense. The catastrophe. Necessary qualifications of the poet.

|

|

Part 3.

|

Construction of the Drama in Sophocles. — Origin of tragedy. Pathos scenes. Messenger scenes. Dialogues. Representation. The three actors. Scope of their work compared with modern actors. Same actor used to strengthen effects. Cast of parts. Ideas of preserved tragedies. Construction of the action. The characters. Ajax as an example. Peculiarity of Sophocles. His relation to the myth. The parts of the tragedy. Antigone. King Œdipus. Œdipus at Colonus. The Trachinian Women. Ajax. Philoctetes.

|

|

Part 4.

|

Germanic Drama. — Stage of Shakespeare. Its influence on the structure of the pieces. Shakespeare’s peculiarities. Its falling action and its weaknesses. Construction of Hamlet.

|

|

Part 5.

|

The Five Acts. — Influence of the curtain on the modern stage. Development of the act. The five parts. Their technical peculiarities. First act. Second. Third. Fourth. Fifth. Examples. Construction of the double drama, Wallenstein.

|

CHAPTER III. — CONSTRUCTION OF SCENES.

|

|

Part 1.

|

Members. — Entrances. Scenes. Units of the poet. Their combination into scenes. Structure of the scene. Intervals. Change of scenery. Chief scenes and subordinate scenes.

|

|

Part 2.

|

The Scenes According to the Number of Persons. — Conduct of action through the scenes. Monologues. Messenger scenes. Dialogue scenes. Different structure. Love scenes. Three persons. Ensemble scenes. Their laws. The galley scene in Antony and Cleopatra. Banquet scene in Piccolomini. Riitli scene. Parliament in Demetrius. Mass scenes. Distributed voices. Battles.

|

CHAPTER IV. — THE CHARACTERS.

|

|

Part 1.

|

Peoples and Poets. — Assumptions of dramatic characterization, creation, and after-creation. Variety of peoples and characters. Germans and Latins. Difference according to poets. Shakespeare’s characters. Lessing, Goethe, Schiller.

|

|

Part 2.

|

Characters in the Material and in the Play. — The character dependent on the action. Example of Wallenstein. Characters with portraiture. Historical characters. Poets and history. Opposition between characters and action. The epic hero intrinsically undramatic. Euripides. The Germans and their legends. Older German history. Nature of historical heroes. Inner poverty. Mingling of opposites. Lack of unity. Influence of Christendom. Henry IV. Attitude of the poet toward the appearances of reality. Opposition between poet and actor.

|

|

Part 3.

|

Minor Rules. — The characters must have dramatic unity. The drama must have but one chief hero. Double heroes. Lovers. The action must be based on characteristics of the persons. Easily understood. Mingling of good and evil. Humor. Accident. The characters in the different acts. Demands of the actor. The conception of the stage arrangement must be vivid in the poet’s mind. The province of the spectacle play. What is it to write effectively?

|

CHAPTER V. — VERSE AND COLOR.

|

| |

Prose and Verse. — Iambic pentameter. Tetrameter. Trimeter. Alexandrine. Verse of the Nibelungen Lied. Dramatic element of verse. Color.

|

CHAPTER VI. — THE POET AND HIS WORK.

|

| |

Poet of Modern Times. — Material. Work. Fitting for the stage. Cutting out. Length of the piece. Acquaintance with the stage.

|

-->

|

| |

INDEX.

|

| |

NOTES.

|

|

|

|

|

Home

• Writing Samples

• Feedback

|